46% of Parents Say Their Child Used Their Credit or Debit Card Without Permission, Racking Up $500+

“Where did that charge come from?”

Nearly half of parents (46%) say that they’ve caught their kids secretly spending with their credit or debit cards without asking, according to a recent LendingTree survey of more than 1,000 parents with children younger than 18. That’s up from 29% of parents who said the same in 2018, when a similar survey was conducted.

Between in-app purchases and one-click ordering — especially in households where family members share devices and passwords — it’s become much easier to use someone’s card without permission nowadays, says Matt Schulz, chief consumer finance analyst at LendingTree.

“Then, you factor in that many of us have spent far more time than usual inside, staring at screens over the past two years, and it makes sense that kids might have used cards without permission a bit more than before.”

And it’s not just innocuous $1.99 charges for extra game tokens: The average amount spent by kids on the sly was $500-plus. Find out what they’re spending on and how moms and dads differ when it comes to kids and credit — plus, get tips on how to safely introduce credit cards to teens.

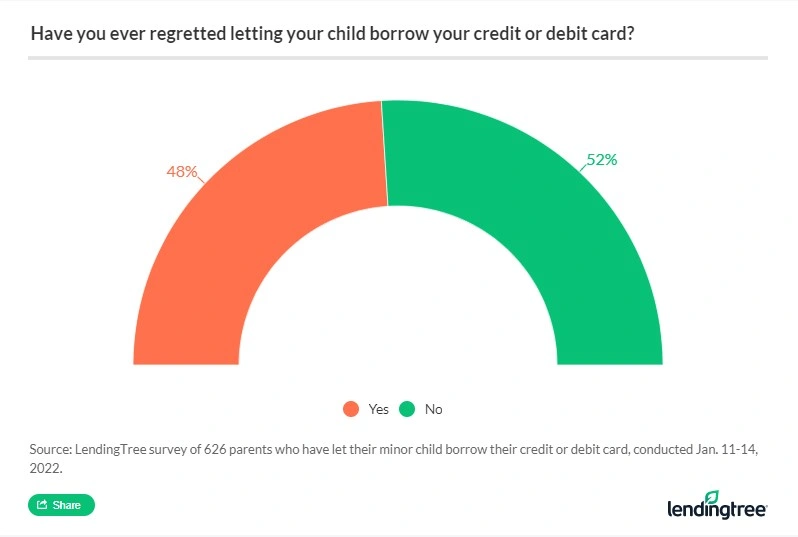

- Six in 10 (60%) parents with children younger than 18 have let their kids borrow their credit or debit cards to make online purchases, and nearly half regret it. Dads are more likely to share their cards with a child than moms, but they’re also more likely to regret doing so.

- Nearly half (46%) of parents with minor children say their child has used their card without permission at least once. That’s a 59% increase compared with 2018, when 29% of parents reported secret spending.

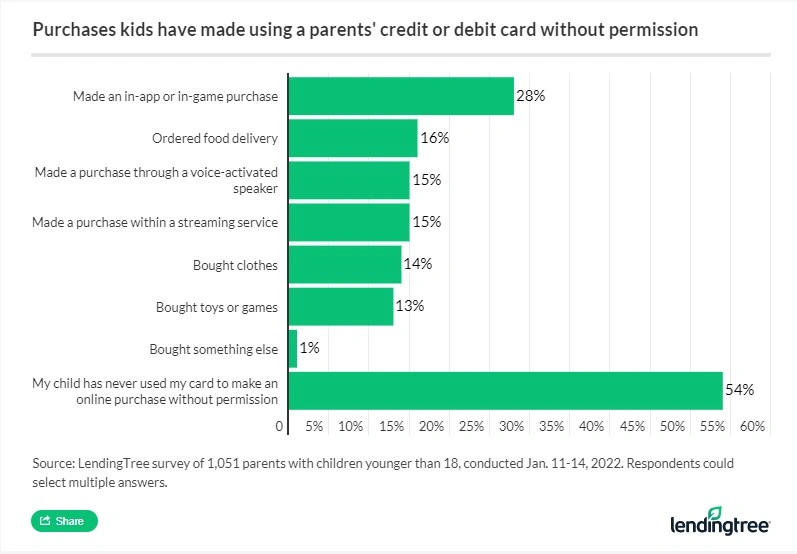

- Kids who took their parents’ credit or debit cards without asking racked up more than $500 on average. Widespread access to tech innovations could be one factor; the most common instances of kids spending without permission include in-app or in-game purchases (28%), ordering food delivery (16%) and purchases made through voice-activated speakers (15%).

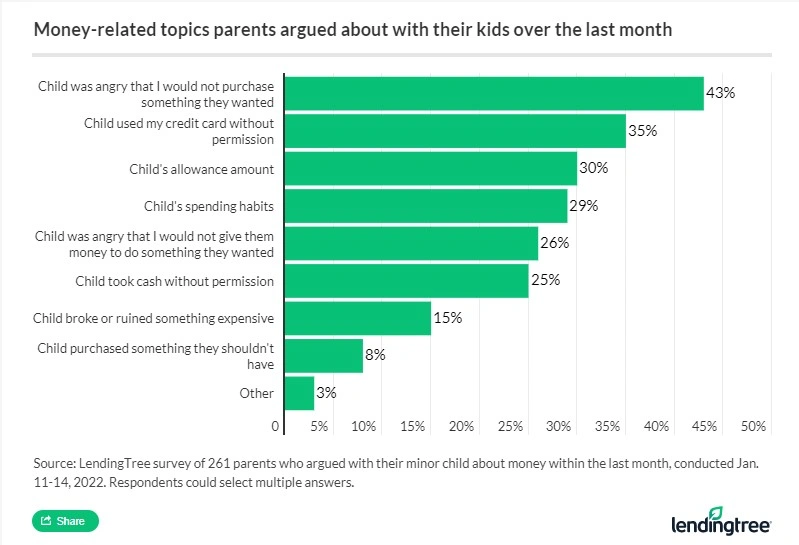

- 1 in 4 parents argued with their child about money last month, and more than a third of arguments were about using a credit card without permission. Taking cash without asking was another source for frustration, at 25%. Dads were more likely to argue with their child about money than moms.

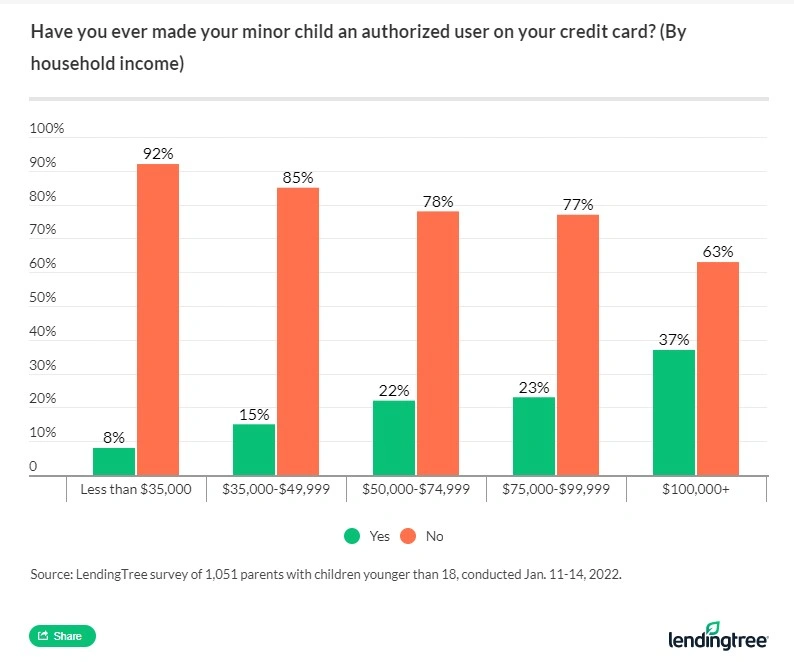

- Kids whose parents earn $100,000+ are nearly 5 times as likely to be an authorized user on their guardian’s credit card than those whose parents earn less than $35,000 (37% versus 8%). Authorized users have a leg up in building credit history (so long as the card is used responsibly), potentially leading to better scores and lower interest rates in the future. Overall, 22% of parents say their minor child is an authorized user.

Parents let children borrow their credit cards, but many regret it

Six in 10 parents said they’ve given their children permission to use their credit or debit card to make an online purchase, dads slightly more so than moms (62% versus 58%, respectively).

As income increases, so does the percentage of parents who were OK with handing off their cards: 68% among those earning more than $100,000 say they are, versus 49% of people with less than $35,000 in annual income.

Giving kids access to plastic often comes with regret, however — 48% of respondents overall have second-guessed that decision, with men more likely to be regretful than women (59% versus 36%).

Kids are racking up major charges without parents’ permission

Almost half (46%) of parents shared that their children have made purchases behind their backs using their credit or debit cards — and it seems to be dads who are swindled more often (58% of them, versus just 35% of moms).

Perhaps the biggest contributing factor is that technology has made it so easy to log in and place an order with a saved payment method. In fact, the most common instances of kids spending without permission include in-app or in-game purchases (28%), ordering food delivery (16%) and making purchases through voice-activated speakers (15%).

It could be that some kids — especially younger ones — may not even realize they’re doing something wrong when they “Ask Alexa” to send over some slime-making supplies or purchase new battle armor for their Fortnite character. “Using a card without permission may not seem the same as taking cash out of mom or dad’s wallet, but it is essentially the same thing,” says Schulz.

When asked about the highest dollar amount that was charged without permission, parents reported an average of $534.

Not only can that betrayal of trust wreck the relationship with a parent, Schulz notes, but that amount can also cause real financial turmoil within families. “So many families are living paycheck to paycheck and have tiny financial margins for error, so when $500 goes missing, that’s a big deal,” he says.

Parents should also make sure that kids understand that this type of behavior could even lead to big legal consequences. “If they were to take money without permission from their friends or their employer or their school, stuff can get real serious fast,” Schulz says.

Charging credit cards without asking leads to arguments

About 1 in 4 parents said they’ve had an argument about money with their kids in the last month — with a higher percentage of dads reporting cash conflicts (30%) than moms (20%).

While there were a range of reasons cited, the second most common argument was over a kid using a credit card without permission.

In order to avoid money misunderstandings and financial fighting, Schulz emphasizes the importance of regular communication.

“It may make for an awkward conversation at the dinner table, but you need to make it crystal clear to your kids what you expect of them when it comes to using your credit or debit card and what the consequences will be if they go off the rails,” he says. “It’s much better to have that conversation in advance when everyone’s calm rather than after the fact, when everyone is anxious and angry.”

Should you let your child be an authorized user on your credit card?

Giving your teen official permission to use your credit card account by making them an authorized user can be a good thing — as long as all parties understand the ground rules. Around 22% of respondents say they’ve done so.

Men (31%) and the highest income earners (37%) were more likely to add a child as an authorized user.

“Being an authorized user can jumpstart a kid’s credit in a way that few things can. You can go from no credit to good credit in a pretty big hurry,” says Schulz. He recommends letting them use the card from time to time under your supervision and make payments on it, so they can get a feel for what it is like before they go out on their own into the real world.

However, it’s important to understand exactly what you’re signing up for when you add a teen (or any authorized user) to your credit account, which 70% of parents in the survey didn’t. They mistakenly thought that even though they were primary account holders, they wouldn’t be fully held responsible for charges made by the authorized user — but that’s not the case.

“The most important thing to know about authorized users is that they are not legally responsible for repaying their balances,” says Schulz.

In other words, if your child is an authorized user on your card and runs up $5,000 in charges on that card, they’re not responsible for it — you are. “Both sides need to understand that very, very clearly from the jump. It’s all about communicating expectations and consequences,” Schulz notes.

Nearly 1 in 6 kids have a credit card in their own name

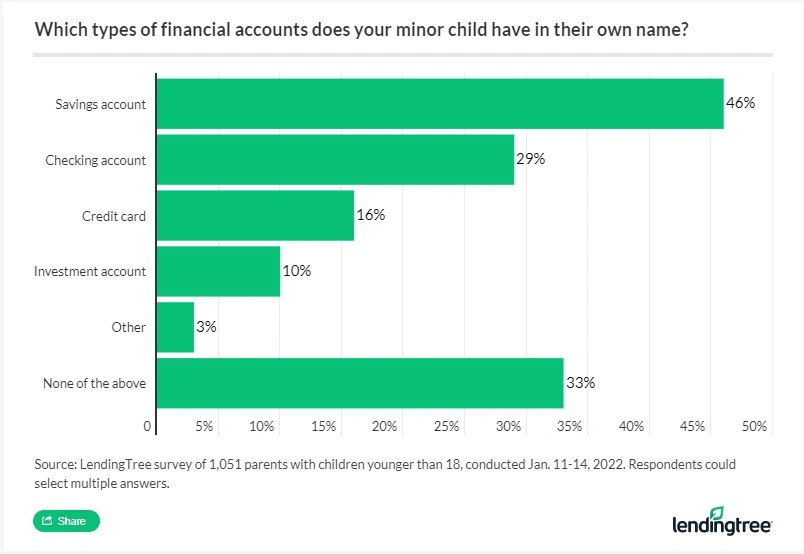

While the most common children’s accounts are savings (46%) and checking (29%), 16% of parents reported that their minor child has a credit card in their own name. Once again, higher family income correlated to a higher percentage of teen credit users, with 25% of those in $100,000-plus households having one (only 9% in the under-$35,000 income bracket do).

“It is your job as a parent to help make sure your kid understands cards, at least at a very, very basic level, before they get the card,” says Schulz. He recommends focusing on the importance of paying on time, what interest is and other key points about credit cards.

Kids and credit cards: 4 quick tips

Building credit from a young age can be a smart move, as long as the card accounts are handled responsibly. Not every kid under 18 is mature enough to have a card in their name, notes Schulz, but there are some steps that you can take to ease them into the world of credit.

- Start with a prepaid or debit card. “Practicing with a prepaid card or a debit card can be a good, low-risk, training-wheels activity for getting comfortable with using plastic,” says Schulz. Parents can then monitor activity and use it as a jumping-off point for conversations about money.

- Make them an authorized user, and keep close tabs. Most card issuers let you track spending through apps, websites, text messages and more. Take advantage of this technology, says Schulz. Bonus tip: If you’re interested in building the kid’s credit early, but don’t think they’re ready, you don’t have to actually give them the card, he adds. “You can simply make the kid an authorized user on the card and let their credit grow quietly in the background,” says Schulz. “Then, when they turn 18 and they’re able to get a card on their own, it will be easier for them.”

- Do a credit 101 lesson with your teen. Explaining how credit behavior can impact their credit score, and in turn, their ability to get a car loan or an apartment in the future is so important, says Schulz. “You have to make it relatable, though,” he adds. “Instead of lecturing them, be on the lookout for teachable moments that you can use as entry points for a conversation about credit and debt.”

- Look for cards suited for first-timers. Schulz recommends student credit cards, which are available once kids turn 18. A secured card can also be useful because it minimizes the risk involved for everyone. “It requires a deposit, which sets the credit limit, so it is a little different from other cards,” he says. “However, because the limit is typically really low, there’s only so off-the-rails the kid can go.”

Methodology

LendingTree commissioned Qualtrics to conduct an online survey of 1,051 parents with children younger than 18, fielded Jan. 11-14, 2022. The survey was administered using a nonprobability-based sample, and quotas were used to ensure the sample base represented the overall population. All responses were reviewed by researchers for quality control.